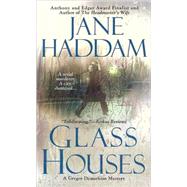

Glass Houses A Gregor Demarkian Novel

by Haddam, JaneRent Book

New Book

We're Sorry

Sold Out

Used Book

We're Sorry

Sold Out

eBook

We're Sorry

Not Available

How Marketplace Works:

- This item is offered by an independent seller and not shipped from our warehouse

- Item details like edition and cover design may differ from our description; see seller's comments before ordering.

- Sellers much confirm and ship within two business days; otherwise, the order will be cancelled and refunded.

- Marketplace purchases cannot be returned to eCampus.com. Contact the seller directly for inquiries; if no response within two days, contact customer service.

- Additional shipping costs apply to Marketplace purchases. Review shipping costs at checkout.

Summary

Author Biography

JANE HADDAM is the author of numerous novels, many featuring Gregor Demarkian, as has been a finalist for both the Edgar and Anthony Awards. She lives in Litchfield Country, Connecticut.

www.janehaddam.com

www.minotaurbooks.com

Table of Contents

Sometimes Henry Tyder thought that the real problem would always be the blood. Bodies could be stashed under tables or cut up and put into trunks. You could take pieces off them or settle for pieces of clothing instead, in case you were worried about how you were going to smell on the bus. Evidence was nothing at all. Evidence was what you made it be. If you wanted it, you went and got it. If you wanted to get rid of it, you had only to point out that you were who and what you were: living on the street half the time; drunk to the gills half the time; out of your mind half the time. No, it was the blood that was the problem because blood went everywhere.

It was five o’clock on the evening of March 23rd, and not as cold as it should have been. A fine drizzling rain had been coming down most of the day. The streets were slick and wet and shiny under streetlamps that were just going on. Down at the end of the block, half a dozen people were huddled near the curb, hoping for taxis. This was not Henry’s ordinary neighborhood. It was not a place where he felt safe.

He checked out the people one more time and then retreated to the narrow alley between two brick buildings. They were the kind of buildings he remembered from his childhood, with stoops at the front and tall windows that looked out onto the city. It was as if the people who lived inside cared not at all about who could see them. On the alley side, though, there were no windows, except one very high up on the fifth or sixth floor. That would have been a maid’s room in the old days. Now it was probably a place where a law firm stowed the kind of files it expected nobody to ever want to see again.

The body was halfway between the two ends of the alley. It was the body of a young woman in a red cloth coat, with fingernails painted to look like American flags. Henry crouched down next to it. His mind was clear. It really was. He’d been living “at home” for weeks now—or at least he’d been living with Elizabeth and Margaret, which was as close as he came to home. He was cold and his bones ached, but he thought he understood what he was doing. The young woman must have been one of those people who liked to call attention to herself. The coat would have stood out in a crowd. The fingernails would have started conversations. Maybe that was what she had wanted. Maybe she had hoped that somebody would make a comment about her nails, some man, and they would talk, and the talk would lead to other things.

Henry got down closer, and looked into her face. Her eyes were open, staring blankly, the way they did when the person who owned them was dead. The side of her face was all cut up. The glass that had been used to do it—thin, wide jagged plates from a glass window, broken God only knew where—was lying around her as if it had fallen from the sky like snow. The glass was covered with blood, and so was the face, and so was the collar of the coat. Blood was in the puddles at the body’s sides, diluted and spread by the falling rain. Henry put his hand out and rubbed his palm across the body’s face. When he took his hand away, it was red and sticky and smelled like something that made his stomach churn.

From here to the end, it was an easy thing: it was just a question of finding a policeman and bringing him here. It would have been easier in the days before most policemen rode around in cars. He picked up one of the small plates of glass and turned it over in his hands. He put it down and picked up another. He picked up the woman’s purse and opened it. She had twenty-six dollars and change in her wallet. He took that and put it in his pockets. She wouldn’t need it anymore, and he did. If he could find some money someplace, he wouldn’t have to face his sisters until he was ready to.

He stood up and looked around. He knew how the woman had died. She’d been strangled from behind with a thin nylon cord people used to tie some kinds of packages for mailing. You found the stuff all the time in Dumpsters. He bent down again and felt around her neck. The cord was buried deeply into the high collar of her jersey turtleneck. It was folded back on itself, but not tied. The cords were never tied. He remembered that from the newspapers. He pulled at it until it came loose in his hands. Then he put it into his pocket with the change.

The drizzle was turning into something heavier. It was so very warm for March, but still cold enough for wet to be something he did not want to be. He leaned over one more time and put his hands in the blood again. He liked the feel of it under the tips of his fingers. He stood up and turned his hands over and let the rain fall on them. The blood washed to the edges, but it did not wash clean.

Henry put his hands in his pockets and started for the street. It was better to go to the street than to the back courtyards after dark. The courtyards were unused and uncared for and often without working lights. Kids hung out in them when they wanted to do drugs and make trouble. He felt the money one more time to make sure it was still there. He came out onto the sidewalk where the people were and looked around.

It was another woman in a red coat who saw him first, an older woman this time, somebody paying attention. Most people didn’t look at Henry Tyder at all.

“Oh, my God,” the woman said, backing away from him toward the stoops. She caught the back of her leg on a step and stumbled. “Oh, my God,” she said again. “Oh, my God.”

A man in a dark raincoat stopped to see if he could help her. “Is there something wrong?” he said. “Is there something I can get for you?”

Nothing succeeds like success, Henry thought. If you looked pretty much all right, everybody in the neighborhood wanted to help you.

That was when the woman started screaming.

Copyright © 2007 by Orania Papazoglou. All rights reserved.

Excerpts

Sometimes Henry Tyder thought that the real problem would always be the blood. Bodies could be stashed under tables or cut up and put into trunks. You could take pieces off them or settle for pieces of clothing instead, in case you were worried about how you were going to smell on the bus. Evidence was nothing at all. Evidence was what you made it be. If you wanted it, you went and got it. If you wanted to get rid of it, you had only to point out that you were who and what you were: living on the street half the time; drunk to the gills half the time; out of your mind half the time. No, it was the blood that was the problem because blood went everywhere.

It was five o’clock on the evening of March 23rd, and not as cold as it should have been. A fine drizzling rain had been coming down most of the day. The streets were slick and wet and shiny under streetlamps that were just going on. Down at the end of the block, half a dozen people were huddled near the curb, hoping for taxis. This was not Henry’s ordinary neighborhood. It was not a place where he felt safe.

He checked out the people one more time and then retreated to the narrow alley between two brick buildings. They were the kind of buildings he remembered from his childhood, with stoops at the front and tall windows that looked out onto the city. It was as if the people who lived inside cared not at all about who could see them. On the alley side, though, there were no windows, except one very high up on the fifth or sixth floor. That would have been a maid’s room in the old days. Now it was probably a place where a law firm stowed the kind of files it expected nobody to ever want to see again.

The body was halfway between the two ends of the alley. It was the body of a young woman in a red cloth coat, with fingernails painted to look like American flags. Henry crouched down next to it. His mind was clear. It really was. He’d been living “at home” for weeks now—or at least he’d been living with Elizabeth and Margaret, which was as close as he came to home. He was cold and his bones ached, but he thought he understood what he was doing. The young woman must have been one of those people who liked to call attention to herself. The coat would have stood out in a crowd. The fingernails would have started conversations. Maybe that was what she had wanted. Maybe she had hoped that somebody would make a comment about her nails, some man, and they would talk, and the talk would lead to other things.

Henry got down closer, and looked into her face. Her eyes were open, staring blankly, the way they did when the person who owned them was dead. The side of her face was all cut up. The glass that had been used to do it—thin, wide jagged plates from a glass window, broken God only knew where—was lying around her as if it had fallen from the sky like snow. The glass was covered with blood, and so was the face, and so was the collar of the coat. Blood was in the puddles at the body’s sides, diluted and spread by the falling rain. Henry put his hand out and rubbed his palm across the body’s face. When he took his hand away, it was red and sticky and smelled like something that made his stomach churn.

From here to the end, it was an easy thing: it was just a question of finding a policeman and bringing him here. It would have been easier in the days before most policemen rode around in cars. He picked up one of the small plates of glass and turned it over in his hands. He put it down and picked up another. He picked up the woman’s purse and opened it. She had twenty-six dollars and change in her wallet. He took that and put it in his pockets. She wouldn’t need it anymore, and he did. If he could find some money someplace, he wouldn’t have to face his sisters until he was ready to.

He stood up and looked around. He knew how the woman had died. She’d been strangled from behind with a thin nylon cord people used to tie some kinds of packages for mailing. You found the stuff all the time in Dumpsters. He bent down again and felt around her neck. The cord was buried deeply into the high collar of her jersey turtleneck. It was folded back on itself, but not tied. The cords were never tied. He remembered that from the newspapers. He pulled at it until it came loose in his hands. Then he put it into his pocket with the change.

The drizzle was turning into something heavier. It was so very warm for March, but still cold enough for wet to be something he did not want to be. He leaned over one more time and put his hands in the blood again. He liked the feel of it under the tips of his fingers. He stood up and turned his hands over and let the rain fall on them. The blood washed to the edges, but it did not wash clean.

Henry put his hands in his pockets and started for the street. It was better to go to the street than to the back courtyards after dark. The courtyards were unused and uncared for and often without working lights. Kids hung out in them when they wanted to do drugs and make trouble. He felt the money one more time to make sure it was still there. He came out onto the sidewalk where the people were and looked around.

It was another woman in a red coat who saw him first, an older woman this time, somebody paying attention. Most people didn’t look at Henry Tyder at all.

“Oh, my God,” the woman said, backing away from him toward the stoops. She caught the back of her leg on a step and stumbled. “Oh, my God,” she said again. “Oh, my God.”

A man in a dark raincoat stopped to see if he could help her. “Is there something wrong?” he said. “Is there something I can get for you?”

Nothing succeeds like success, Henry thought. If you looked pretty much all right, everybody in the neighborhood wanted to help you.

That was when the woman started screaming.

Copyright © 2007 by Orania Papazoglou. All rights reserved.

Excerpted from Glass Houses by Jane Haddam

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.

An electronic version of this book is available through VitalSource.

This book is viewable on PC, Mac, iPhone, iPad, iPod Touch, and most smartphones.

By purchasing, you will be able to view this book online, as well as download it, for the chosen number of days.

Digital License

You are licensing a digital product for a set duration. Durations are set forth in the product description, with "Lifetime" typically meaning five (5) years of online access and permanent download to a supported device. All licenses are non-transferable.

More details can be found here.

A downloadable version of this book is available through the eCampus Reader or compatible Adobe readers.

Applications are available on iOS, Android, PC, Mac, and Windows Mobile platforms.

Please view the compatibility matrix prior to purchase.